Collections by topic / Slavery

As from the start of the 18th century, slavery developed on Reunion Island, situated along the trade route for coffee and spices, as it did elsewhere in the Indian Ocean. Slaves, both domestic workers in the towns and agricultural labourers on the plantations, represented an important percentage of the population of Bourbon island, which counted 49,369 slaves in 1815, compared to 18,940 free citizens. As on the other large plantations on the island, a large number of slaves – 295 listed in Madame Desbassayns’ will – worked on the Panon-Desbassayns estate in Saint-Gilles. This servile workforce notably contributed to the success of the estate’s new sugar factory, which, when it was opened in 1827, was considered to be an example of modern technology.

Until 1848, the lives of the slaves on Bourbon Island were determined by the document Lettres de patentes en forme d'édit concernant les esclaves nègres des Isles de France et de Bourbon (Patent letters issued as an edict regarding the black slaves on the islands of Ile de France and Bourbon), in fact the Code Noir (legal code) applicable to Caribbean Africans enacted in 1685 by Louis XIV, amended in 1723 and registered in Saint-Paul on 18th September 1724. The document defined slaves as being ‘movable goods’ that could be bought, sold, rented or seized, according to their masters’ wishes. Cut off from his original culture and deprived of his legal rights, the slave could own nothing and became the property of his master, who controlled everything he did, and he or she was subject to the organisation of the estate where he or she lived and worked. Punishments commonly consistent of whippings and while unions between men and women were tolerated, the condition of slave was handed down by the mother to the children resulting from such a union.

Immediately preceding the opening of the sugar factory on the Desbassayns estate, a census carried out on the island registered some 62,000 slaves. To this number must be added the clandestine slaves mainly unloaded from ships sailing in from Madagascar and the East African coast. In 1827, the year when the sugar factory was opened, the slave trade had been considered as illegal by Britain and its colonies for 20 years and for 10 years by France. However, clandestine trading continued, ensuring a continuing supply of slaves to the colony, with some 45,000 slaves between 1817 and 1848. The severe repressive measures applied by the government under Louis-Philippe meant that clandestine trading became very risky as from 1831, then virtually impossible as from 1840. The decreasing workforce during the period when the sugar industry was booming meant that the tasks to be carried out became even tougher.

See the collection

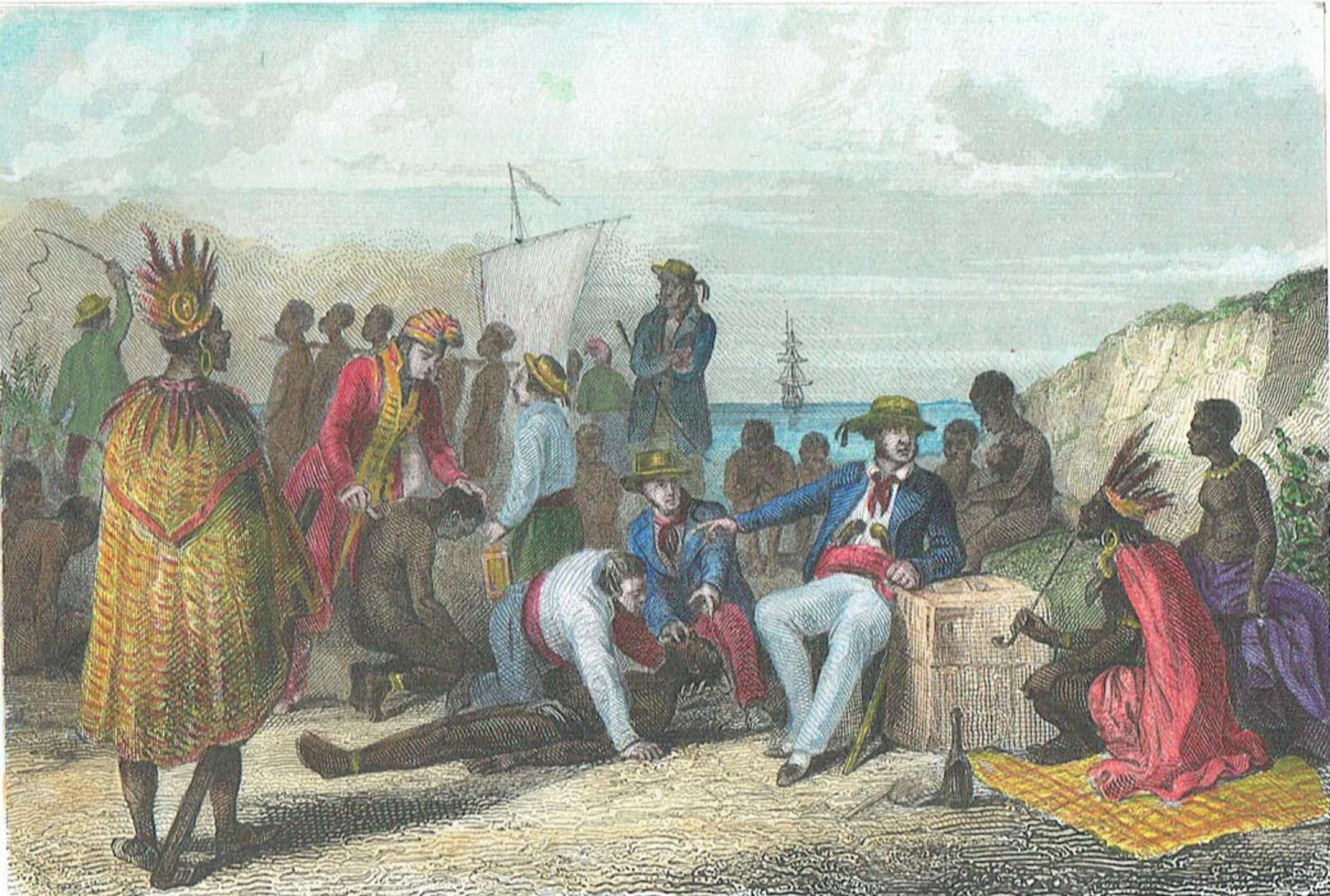

Zanzibar, comptoir musulman, était un centre important de la traite négrière de la côte orientale de l'Afrique. Il devient une source importante d'esclaves pour Bourbon à partir de l'an X du calendrier républicain (1802), après le rétablissement de l'esclavage dans les colonies françaises par Bonaparte.

Inv. 2018.2.26

Côte Est d'Afrique, commerce des esclaves à Zanzibar

(East coast of Africa, slave trade in Zanzibar)

Lechard, based on a drawing by Hemy, 19th century.

Chisel engraving H. 13 x L. 18 cm

These glass beads, found in the ocean off the coast of Mauritius, were used in the slave trade, exchanged for captive African slaves.

However, suppliers very soon asked to have these trinkets replaced by metal bars to be used for the manufacture of weapons and tools, as well as Indian cloth or alcohol. The gun used for the slave trade, with its long barrel and flint lock, was also an object of exchange often demanded by slave hunters, enabling them to supply a larger number of captives.

See the entire set

Inv. 1998.4.1 à 14

Beads used in the slave trade

Glass, various sizes

Inv. 1998.5.1

Model boat, L'Aurore, slave ship 1784

Timber and cotton

H. 101,5; L. 133,5; W. 29 cm

This model slave ship was constructed on the basis of a wealth of documents including texts, sketches and more or less detailed plans from the collection of Hubert Penvert, an engineer and constructor from la Rochelle, who died in Angoulême in 1827. These documents were the object of detailed research carried out by Jean Boudriot at the archives of the Port of Rochefort and published in 1984.

Designed in 1784, the ship, with a registered tonnage of 280, had a length of 100 ft and a width of 26 ft. It was destined to sail to the coast of Angola, a Portuguese possession that was a hub of the slave trade.

It should be noted that in his work La Route des îles, contribution à l'histoire maritime des Mascareignes, Auguste Toussaint mentions a ship named l’Aurore by name, a French vessel with a registered tonnage of 250 that made two return journeys in 1786 and figured in the list of the 261 vessels registered at the île de France between 1773 and 1809. Jean-Michel Filliot also mentions a ship named Aurore arriving at the île de France at the end of June 1789, after remaining anchored for a time at Cadix.

L'Aurore could transport between 600 and 650 slaves, as well as its crew of 40 to 45 men. The slaves occupied the lower deck, for the occasion equipped with a retractable scaffold. This intermediate level, constructed using planks laid down crosswise, could hold 120 persons (80 children and 40 adults). According to Boudriot, each of the slaves, lying down on his or her side and placed head-to-toe, disposed of a space measuring one third of a square meter.

At the time of abolition, slavery also became a source of inspiration for certain French artists, enabling them to assert their own ideas or represent scenes from their imagination and for certain artists, it allowed them to give expression to their fantasies.

In this respect, the sculpture by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux entitled Pourquoi naître esclave (Why be born a slave), acquired in 1992, and the double-glazed bronze by Edmond Louis Levêque entitled Les deux esclaves (the two slaves), acquired the following year, are two remarkable examples of this artistic current.

Collections by topics / Indentured labour

Indentured labour – free workers under contract coming from India, Africa and China, then later the Comoros, Madagascar, Oceania and Rodrigues – represented an attempt to compensate for the shortage of labour as from the first half of the 19th century, though it proved difficult to organise slave labour and that of free workers on the same estate. After slavery was abolished in 1848, indentured labour became common, with the number of indentured workers higher than the number of slaves freed in 1848, with 37,777 Indian labourers, 26,748 Africans and 423 Chinese. However, during the 19th century, the system came under a number of restrictions due to the ill treatment of indentured labourers and breaches of contract. Recruitment of indentured labourers from India was finally suspended for good in 1882.

Study and analysis of various documents by historians have revealed the deceptions applied by recruiters until the end of the 19th century. Along the coasts of Africa and Madagascar, the indentured workers were in actual fact men who had been captured and sold by Arab traders to recruiters from Reunion, who would free them before signing their contract. The driving force behind this system was fear. While hopes of a better life represented the main incentive behind departure for those referred to as coolies, or Indian indentured workers, kidnapping and deceit now became common techniques for shipping these men to Reunion, in conditions similar to those of slavery.

Before abolition, these labourers generally worked alongside the slaves, in conditions that were no less difficult. The King’s public prosecutor, in a report addressed to the Ministry of the Navy and the Colonies, wrote: “few inhabitants have really understood the position of these free workers. Virtually everywhere, they are treated like slaves on the estate.” Like the slave, the indentured worker, through his contract, remained the property of his employer. Corporal punishment was common and very often salaries were not paid. It is easy to understand, therefore, why "maroonage" – slaves escaping to flee their condition – remained a common element of the system of indentured labour.

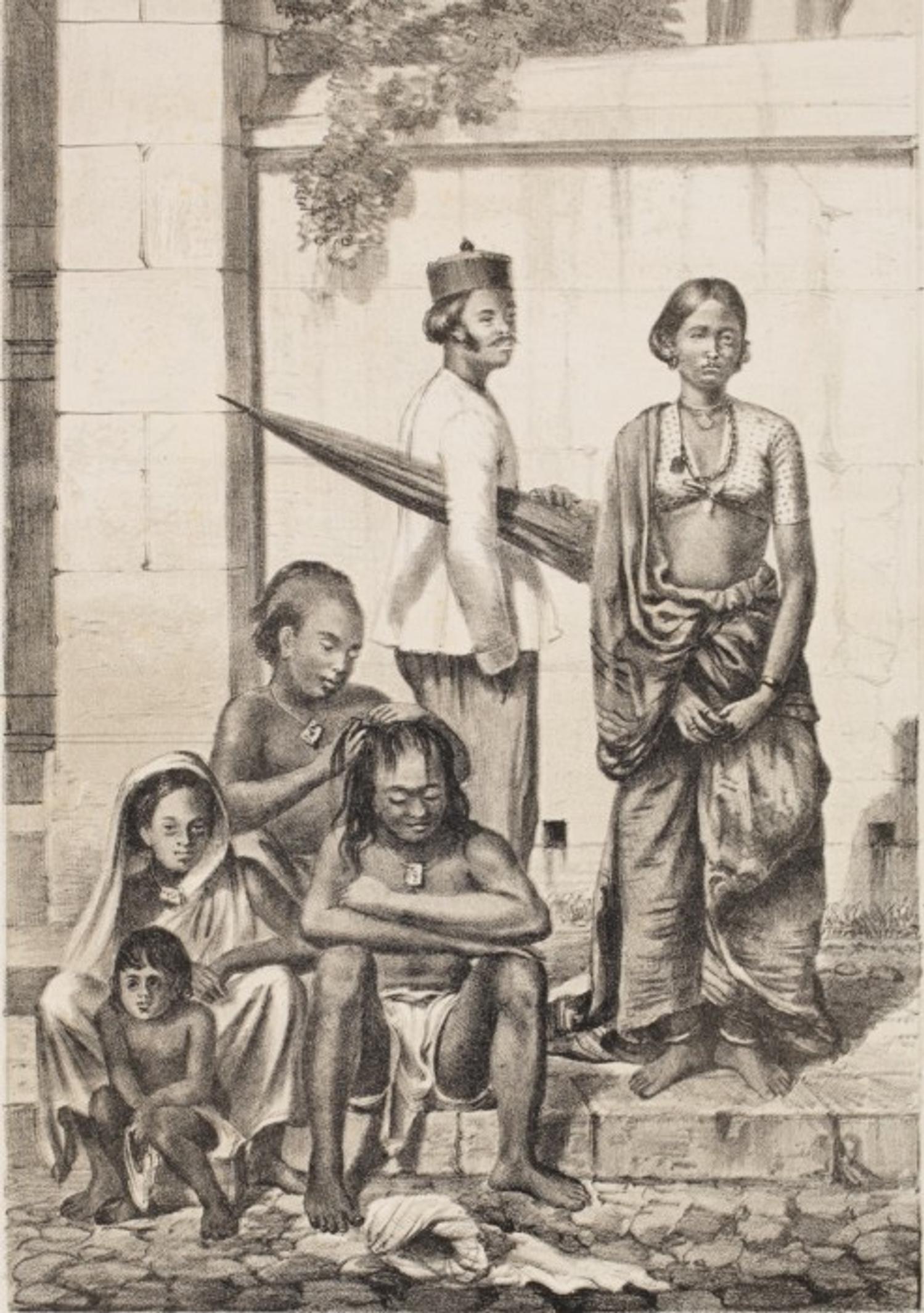

This lithograph illustrates two social categories of Indians: in the foreground, newly arrived indentured labourers in Reunion represent extreme poverty, contrasting with the glaring social success of the Indian couple depicted in the background.

Indeed, at the end of their five-year contract, the Indian indentured labourers were authorised to remain on the territory and could build a better life for themselves if they wished to do so.

This social success must, however, be seen against the accounts of maroonage (escaping) reported in the local press at the time. Sudel Fuma, who studied the phenomenon in his work L'esclavagisme à La Réunion 1794-1848, (Slavery in Reunion 1794-1848) summarised the situation: "[...] less than two years after arriving in the colony, most of the Indian labourers abandoned their employers, preferring to live as vagabonds rather than put up with the discipline applied on the large estates.”

Inv. 1998.8.9.2

Types des immigrants indiens (Types of Indian immigrants); Album de La Réunion

Antoine Roussin, lithographic printing press 1863

Lithograph

H. 30,5 x L. 22 cm

Inv. 1990.125

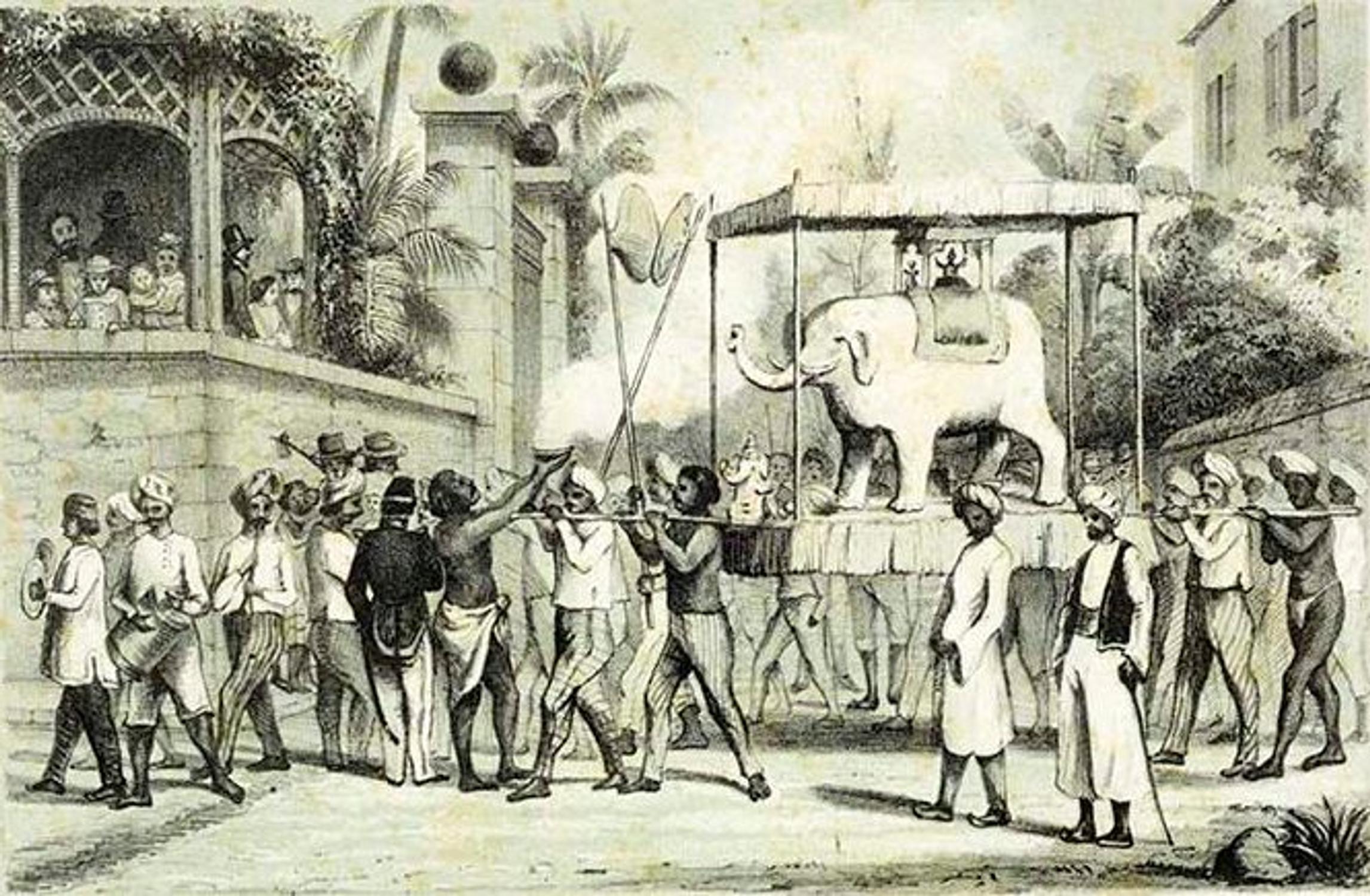

Fête des travailleurs indiens (Indian workers’ festival); Album de La Réunion

Paul Eugène Rouhette de Monforand and Antoine Roussin, 2nd half of 19th century

Two-colour lithograph

H. 23 x L. 31 cm

As from 1830, just when the development of intensive sugar production necessitated a greater and greater workforce, the government of Louis-Philippe severely condemned the slave trade and encouraged policies aimed at the emancipation of slaves.

From then on, engaged labour was seen as a source of hope. After abolition in 1848, it became a necessity for all the colony’s sugar producers. Aware of the cultural identity issues created through the introduction of Indians on Bourbon island, in a letter dated November 1830, the Minister of the Navy and Colonies recommended that “a large degree of tolerance should be applied regarding these foreigners, who should be allowed to practice their customs regarding burials and successions.” (cf. Sudel Fuma, L'esclavagisme à La Réunion, 1794-1848, Paris, 1992).

On this lithograph, the celebration of an Indian religious festival is the occasion of a low-scale regulated event, enabling the workers to avoid being totally cut off from their cultural traditions. The procession, headed by a group of musicians, attracts the interest of a family passing by, who appear curious and perhaps a little alarmed. We can easily recognise the presence of the nénène (nanny) carrying the youngest member of the family, who are watching the event from a kiosk constructed along the top of the boundary walls of a bourgeois property with its impressive gateway.

. Voyages of exploration and colonial conquests

. Voyages of exploration and colonial conquests