Collections by topics / Contemporary art

Without representing a major aspect of the museum’s acquisition policy, contemporary artistic production does, however, play a major role in the collections of the Villèle museum. An initial collection of non-European art allows us to retain links with cultures at the origin of the Reunionese identity, while a local collection gives a sensitive and personal reading of the history of the Panon-Desbassayns estate, of slavery or, more widely, Reunion in general.

Contemporary art / local collection

Wilhiam Zitte

Inv. 1993.40

Pietà, Wilhiam Zitte, Antoine du Vignaux, 1992

Acrylic / goni (burlap)

H. 110 x L. 250 cm

Pietà was created for the exhibition Tet Kaf / Fet Kaf (African head / African festival) held at the Villèle museum en 1992. For the occasion, Antoine Du Vignaux and Wilhiam Zitte presented several images of black men and women, a commemoration and a reflection on slavery and its scars. The central element of an installation consisting of three triptychs, each of which occupied one of the rooms in the slave hospital, Piéta presents a ‘spiritual black’, who could well point to a third possible way forward, contrasting with the ‘faithful black’, submissive under the yoke of pain and self-sacrifice, or the ‘rebel black’, whose weapons stir up the fire in the still glowing embers.

Painted on the same jute sacking that was used to carry coffee and sugar, both crops dependent on slavery, Zitte’s Pietà clearly depicts the mixed racial nature of her Creole identity and the simplicity of her origins. On her lap she has two inert intertwined bodies, one recalling the Christ of Michelangelo’s Pietà and the other, more anonymous, is more robust and anchored, as if to better bring down to earth the pain incarnated by a martyrdom that has already become ethereal.

The many repentances cause the mother’s legs to oscillate from one son to the other, seemingly wishing to envelop everything in her arms, omitting no element of this accumulation of history and events which are, however, slipping away, or of the cultural intermingling behind the construction of the Creole, an individual born out of all these layers and still in the process of becoming.

On either side of the scene, two abstract panels created by Antoine Du Vignaux frame the central panel like scenery in Pompei, a reference to those frescoes recalling the remains of an ancient civilisation, rediscovered while carrying out an archaeological dig. The effects of gleaming materials bursting out of the frame enable the work to breathe, one window remaining open onto a long buried past, another opening onto a future still to be written.

Laetitia Espanol

Inv. 2000.2.4

Zélie, créole, pioche, Ann-Marie VALENCIA, 1999

Peinture acrylique et papier marouflé / toile

H. 123 x L. 61 cm

Ann Marie Valencia

Ann Marie Valencia was a painter outside time and artistic styles. Nevertheless, the works displayed at the Villèle museum for her exhibition Aurélie, Betzy et les autres... (Aurélie, Betzy and the others) (1999) recall a tragic buried past, but one during which Woman and Nature existed in harmony.

Recollections of women … Women who ran the estate: Ombline Desbassayns (1755 - 1846), with a firm hand; Céline de Villèle (1820 - 1896), with submission; Lucile (1901 - 1976) and Pauline (1902 - 1990) de Villèle, with self-sacrifice.

There is also the recollection of those faceless women, still present through being summarily mentioned on the yellowed paper of documents in the archives: a more or less fanciful family name given arbitrarily by the dominating society; a function, largely lacking in originality, but sufficiently evocative to remind us of practices during the period of slavery; a vague ethnic origin with its roots lost in the imprecise or even totally unknown location; finally, she was property with a monetary value, a sordid indicator of wealth which, with hindsight, appears to us as derisory as it is indecent.

The recollection of a recent past has, however, left its mark on our memory. The recollection of a continuously transformed domestic landscape that, with time, mingles cotton, coffee, spices and sugarcane.

Ann Marie Valencia reconstructs a universe inhabited by women who are beautiful, so beautiful when carrying out their thankless tasks and their harrowing daily chores. Her works present us with the delicacy of a style showing great maturity. The intelligence of her vision recreates for us the contrasted beauty of these faces, marked by repetitive hard labour. Even if her light brushstrokes, as light as rose petals, come to delicately caress the canvas support with its subtle covering of lightly creased-up tissue paper, the artist makes no concessions with effects that could be seductive for their own sake. Behind the work of art lies the artistic commitment of a totally authentic painter and the tender and respectful vision of the woman, representing the Woman in general. Ann Marie Valencia applies the colours of her emotions to reconstruct in her own way the exhumed and magnified fragments of a painful chapter of history that has not yet revealed all its secrets.

Nelson Boyer

On a different level, four works by the sculptor Nelson BOYER have been acquired by the museum, partly purchased and partly donated by the artist.

The bronze sculpture Moringueur (moraingy dancer) depicts a person practising a martial art inherited from slavery, defying the laws of gravity to totally immerse himself, body and soul, in this ancestral practice. Another work entitled Marron (escaped slave), a terracotta sculpture, fixes the desperate escape of a fleeing slave, carrying with him the slave-collar representing his servile condition. Nelson BOYER, with his extreme sensitivity, ignores all conventions to revisit his island’s dark history.

A self-taught sculptor, Nelson Boyer practices his art without following academic rules. The figures created express the same pain, the same suffering and the same resignation. Matter echoes emotion. The artist is able to express, through matter and using his own specific language, what could never be expressed so deeply simply using words. His tortured sculptures, through their intense expressive force, show recurring spontaneity, freeing themselves from realistic or naturalistic patterns to claim total liberty of form. Thus, any anatomical anomalies are of no importance, being above all at the service of the idea. They are born out of a different reality, a reality that is situated outside normal standards. Quite to the contrary, when Nelson is more realistic in his work, sacrificing it to the tension of detail, his works lose their expressive power, becoming anecdotal.

While Nelson Boyer is a great admirer of Carpeaux – his presence at the historical museum to enable him to see close up the bronze work entitled Pourquoi naître esclave ? marked an important event – his work, focusing on massive forms, owes more to Bourdelle. Nelson is a very sensitive artist who has rejected all conventions to claim – or rather to cry out – his own history and that of his island. In the earth, he has found the material, notably sandstone, that he works with to liberate his creative energy and give form to his sensitivity.

Inv. 2006.11

Marron (escaped slave), Nelson Boyer, 2005

Terracotta and engobe

H. 22 x L. 20,5 x P. 23,5 cm

Contemporary art / Art from outside Europe

Since it reopened in 1990, the Villèle museum has aimed to reinforce its historical role. However, without denying the important elements of the founding principal behind its creation, it has progressively been opening out to the cultures of other Indian Ocean islands and countries, more particularly East Africa. The Reunionese society being a multicultural one, the museum has set up a process aimed at presenting to the island’s population windows opening out onto the cultures of countries where certain members of the population have their roots.

Thus, in 1999, a coherent series of 52 paintings on canvas by Tanzanian artists came to enrich the collections of the Villèle museum, for the exhibition Tingatinga ou les Makua de la modernité. Entitled TINGATINGA, the name of the self-taught artist behind this artistic production, this artistic movement, still very active to this day, is represented in the collection by works created in 1998 by 39 painters from three distinct groups based in Dar es Salaam.

In 2000, at the initiative of the Indian Cultural Relations Council, was held an important exhibition of paintings from the region of Mithila, now called Madhubani, one of the ancestral artistic forms of expression in the state of Bihâr in the North East of India. For this occasion and following an artistic residency at the museum, 26 works were acquired, consisting of nine drawings by MUDRIKA Dévi and 17 by CHANDRA BUSHAN KUMAR, respectively representing both the tradition and the modernity of this popular art, which achieved international recognition in the 1970s.

The museum’s collections were then enriched by another collection devoted to Mozambican works by the Makondé tribe, in the context of the exhibition Dominique Macondé, co-produced by the Villèle museum, the national art gallery of Maputo (MUSART) and the National Ethnological Museum of Nampula (MUSET) in 2006. Since this important cultural event, collectively organised between Reunion and East Africa, wooden sculptures by confirmed artists have figured in the museum’s inventory, these artists being Miguel VALINGUE, Lamizosi MADANGUO, a remarkable series of 16 terracotta ceramics by Reinata SADIMBA, as well as a 22-piece convoy of slaves by Miguel Cristovao Carlos NTCHULU.

Finally, in 2010, the collection of Indian works was once more enriched, thanks to the acquisition of six drawings by Nilesh Brahmachari.

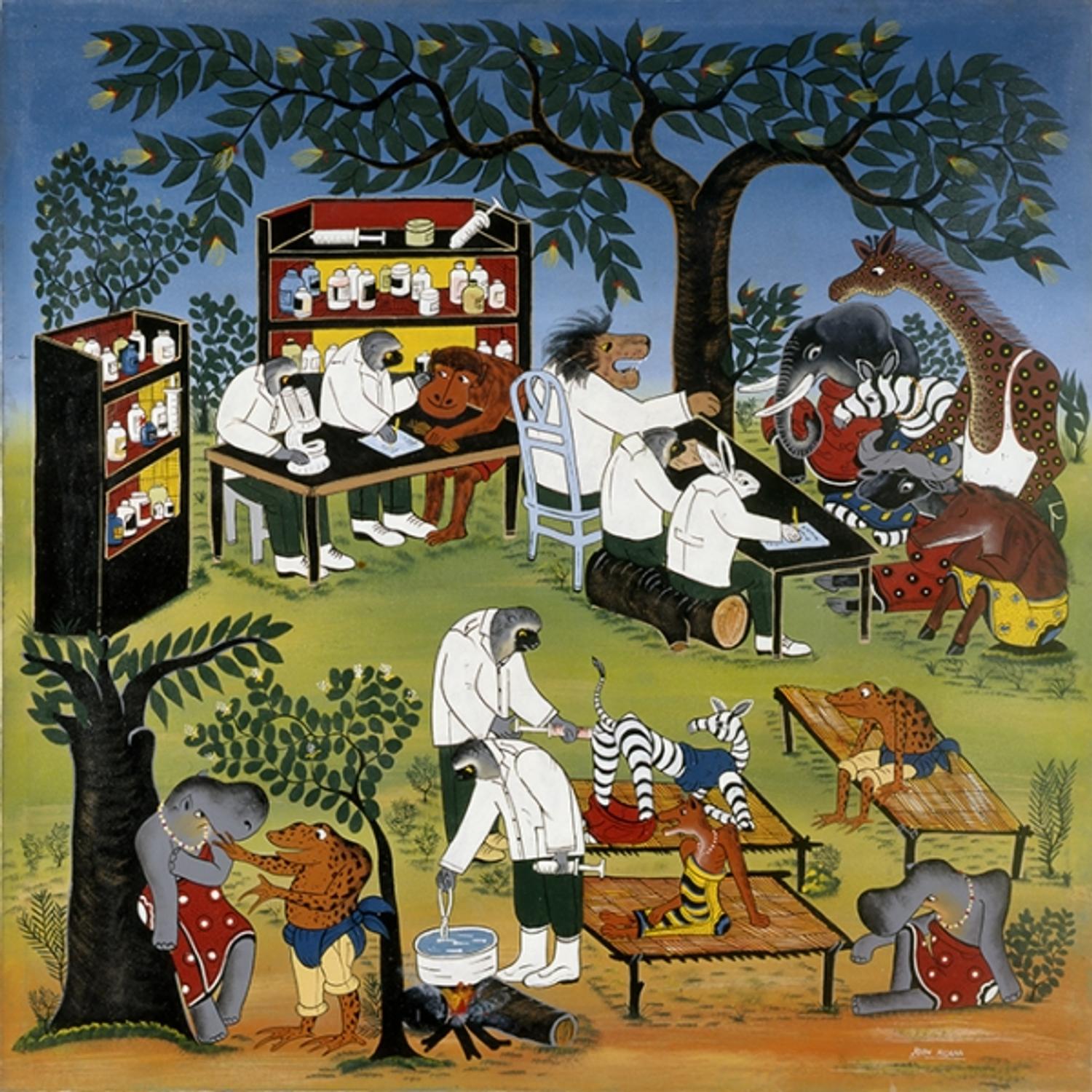

Tingatinga, Tanzanie

Inv. 2000.1

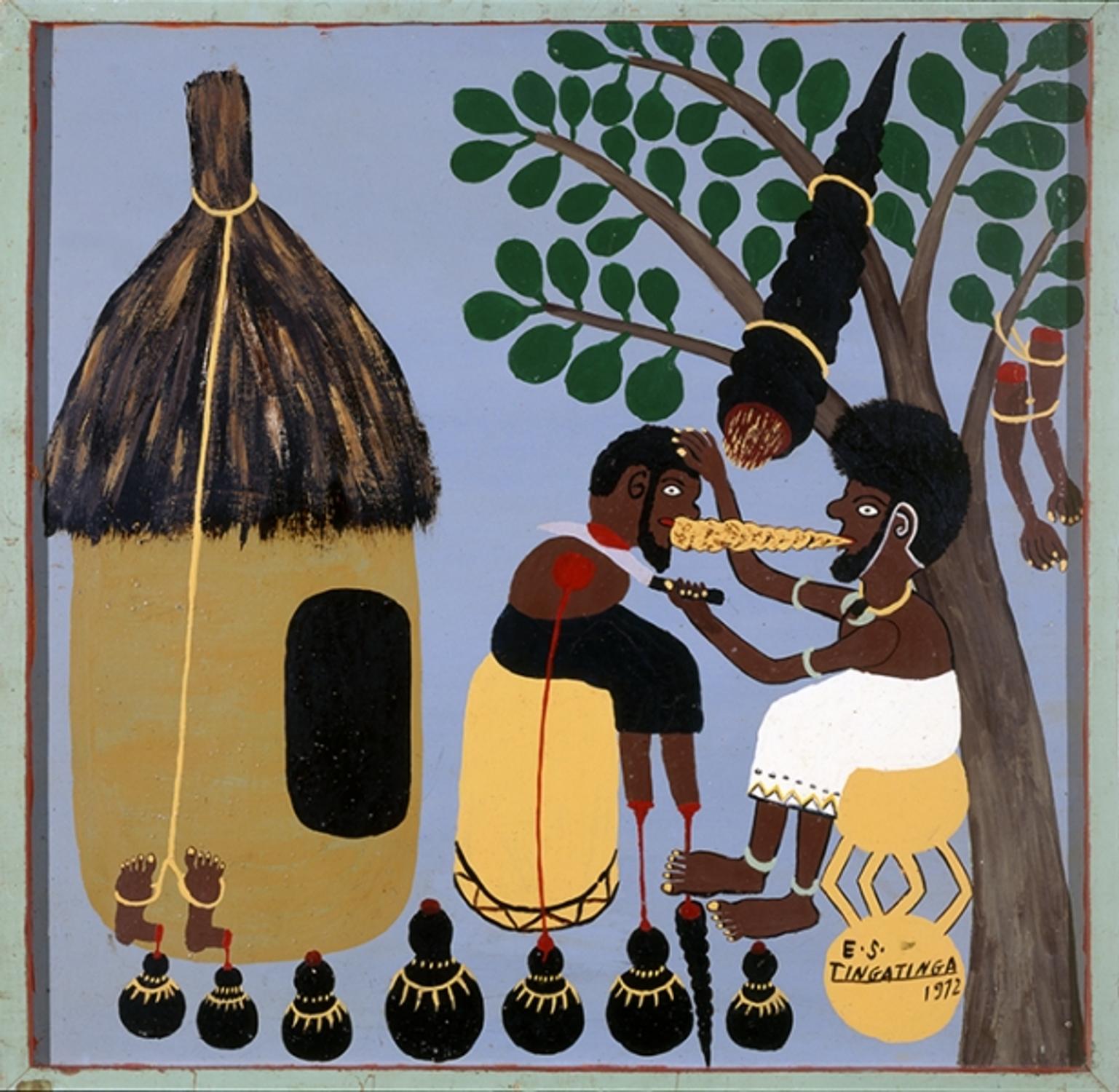

Guérisseur, (Healer), Tingatinga Edward Saidi, 1972

Lacquer / wood and isorel

H. 60 x L. 60 cm

Edward Saïd Tingatinga began to paint in the 1960s, when Tanzania was no longer under the yoke of British colonialism. After independence, granted in 1961, Tanzania had to build its future on a new basis and despite an unfavourable economic context. The task was a huge one and the country, under the president of the republic Julius Nyerere, resolutely adopted a socialist-style political system, advocating national unity and focusing on health and education.

In the context marked by the economic crisis affecting people’s daily lives, Edward Saïd Tingatinga, from the region of Tunduru, like many other inhabitants who had left regions situated in the south of Tanzania, was attracted to Dar es Salaam. Initially, he attempted to hire out his services, first of all to resident Europeans as a domestic worker, then later as a receptionist in one of the town’s hospitals. In search of his vocation, he started painting, without ever having learnt the techniques and without having any true references, with the exception of the traditional painted walls of his region and with no masters other than a gift for drawing and the determination to succeed.

His compositions, where representations of animals play an important role, as well as, to a lesser degree, scenes from daily life, are appreciated for their simplicity and natural character. The patterns are created using gloss paint applied onto square sheets of hardboard. Initially, his pallet of colours was restricted, then was enriched with bright contrasting hues. Partly thanks to the success achieved by his works, Edward S. Tingatinga founded, within his family, an art school combining art and handicrafts, where students learn without learning, but through observation and by re-appropriating works already created by the teacher. Some of the pupils, for example Ajaba, Mpata or Mruta, continued the work of the school’s founder after his death, which occurred prematurely in 1972 in a road accident. Others, such as Kainne, have decided to abandon the activity in favour of a different profession.

Some consider that it would be easy and reductive to qualify Tingatinga’s style as being naïve. Each composition is a true hymn to life, presenting a vision of an imagined colourful world where patterns float against a background with no perspective. In many ways, the style of Tingatinga’s painting has a Romanesque aspect and in this respect reflects the charm of certain Mediaeval illuminated manuscripts, retaining, nevertheless, its own style.

Inv. 1999.1.45

AIDS, Kilaka John, 1998

Lacquer / canvas

H. 99 x L. 99 cm

For several decades, Tingatinga’s works have been the object of a number of artistic events in Africa (Tanzania, Swaziland and Kenya), but also in Switzerland, Canada, Japan, Finland, Denmark, Germany and France.

The artists invited to display their work at the Tingatinga ou les Makua de la modernité exhibition at the Villèle museum in 1999 come from three distinct groups in Dar es Salaam, in the neighbourhood of Morogoro Stores and within the perimeter of the museum village: the Tingatinga Arts Co-operative Society Limited, an association founded in 1976 by members of Edward S. Tingatinga’s family, the Chama Cha Wandomo association (Chama Cha Wafanyabiashara Ngodo Ngodo Morogoro Stores) and the Freelance Artists Studio.

While each workshop has its own technique for preparing the canvas, several stages are essential for the creation of a work, stages shared by different artists. Initially, white canvas is stretched over a wooden frame. A mixture of flour and water (uji) or wood glue and coconut oil is applied to the canvas to enable the paint to adhere more efficiently. After drying, the surface of the canvas is polished, after which the painter applies a layer of red oxide, thus completing the process of preparing the support. The next stage is the background and then the different patterns of the chosen subject, applied directly with a brush, or first of all sketched out with a pen. The painter then proceeds to apply the layers of paint and, after each stage of the work, the painting is left to dry in the sun. The artists often produce two or even three works at the same time, alternately working on each of his or her canvases.

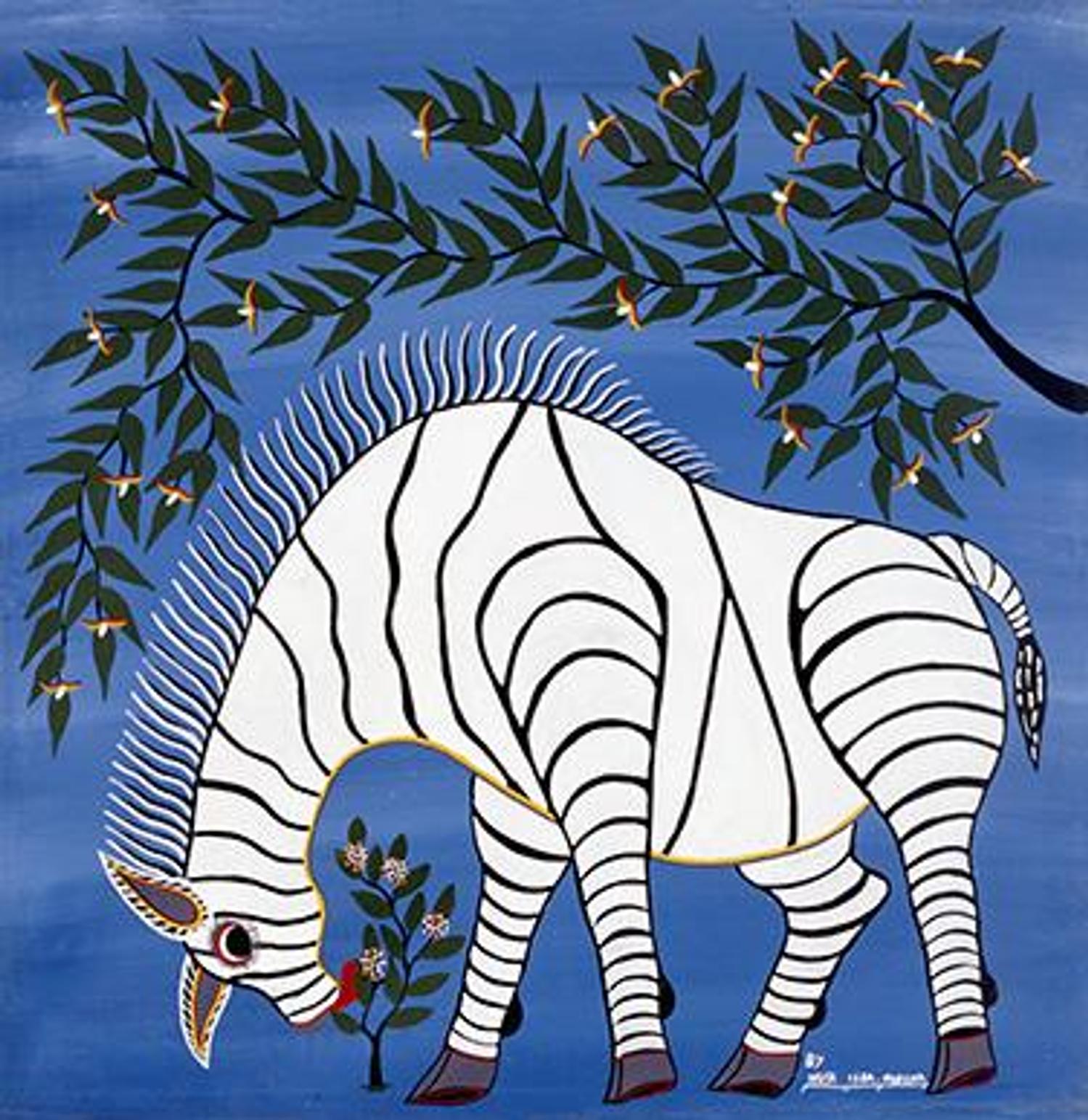

Inv. 1999.1.47

Zèbre, (Zebra) Busungu Benjamin, 1998

H. 60 x L. 60 cm

Lacquer / canvas

Three categories of subjects are treated. Tanzania’s wild animals and the rich fauna are the first topic. These paintings, very often stylised, show little realism. The subject is at times represented alone against a more or less elaborate background and at others carefully organised in various combinations, regardless of any perspective. The second category consists of scenes from everyday life, showing traditions (village customs, harvesting of cashew nuts, healers etc.), the importance of sacred ceremonies (initiation ceremonies of adolescents) or focusing on a relationship with the world based on magic (sorcery). They also reveal the effects of modern life (corruption, AIDS, publicity etc.) which are destroying today’s society. To better communicate their messages, painters also represent humanised animals, drawing from the oral tradition of popular tales. More enigmatic and focusing both on the exploration of the unconscious and the expression of ancestral fears, the shetanis or demons (both good and evil) put on a performance with their macabre dances and their cannibalistic orgies, as though to remind us of our limitations and inconsistencies.

In this way comes to life before our eyes a country not unfamiliar with the marvellous, a richly coloured world peopled with small friendly amusing figures, charming or moralising animals and lively spirits, playful but frowning and threatening.

The art of Makondé, Mozambique

Inv. 2006.6.2

Shetani Namayekala, Madanguo Lamizosi, 2006

Sculpture, ebony wood

H. 55 x L. 15 x P. 16 cm

When Mozambique achieved independence in 1975, a new form of artistic expression asserted itself. It was the product of a number of sculptors who had emigrated and were now returning to their mother country, enriched through the experiences acquired abroad. Some had already become well-known on the international level.

The sculptors selected to present modern Makondé sculpture for the Dominique Macondé exhibition (Villèle museum, 2007) belong to different generations. Some were born in the late 1940s or early 1950s and were just children at start of the liberation movement in 1964.

Only Labus SHIJELU was already an adult. Two young sculptors, Félix Jaime MOAMEDI et Miguel Cristovao NTCHULU, were born after 1975. Some of them lived in the province of Cabo Delgado during the war years. However, we can say that during this period their artistic production was not significantly affected by the changes that took place in Mozambique. They learnt the art of sculpture in a family context, since most of them came from families of the artists. The enthusiasm of the first years following independence and the interest their art attracted all over the country created an atmosphere conducive to their development and that of their creativity as sculptors.

Despite this favourable context, the difficulties encountered when it came to commercialising their artistic productions and the new outbreak of war in the 1980s had a greater influence on their production, while at the same time limiting the display and promotion of their works. However, a few important exhibitions were organised nationally and internationally, such as the exhibition Art Makondé : tradition et modernité, held in Paris in 1989. Lamizosi MADANGUO and Miguel VALINGE, both exhibiting at the Villèle museum, belong to the group of artists that became known during that period and who continued to actively produce works.

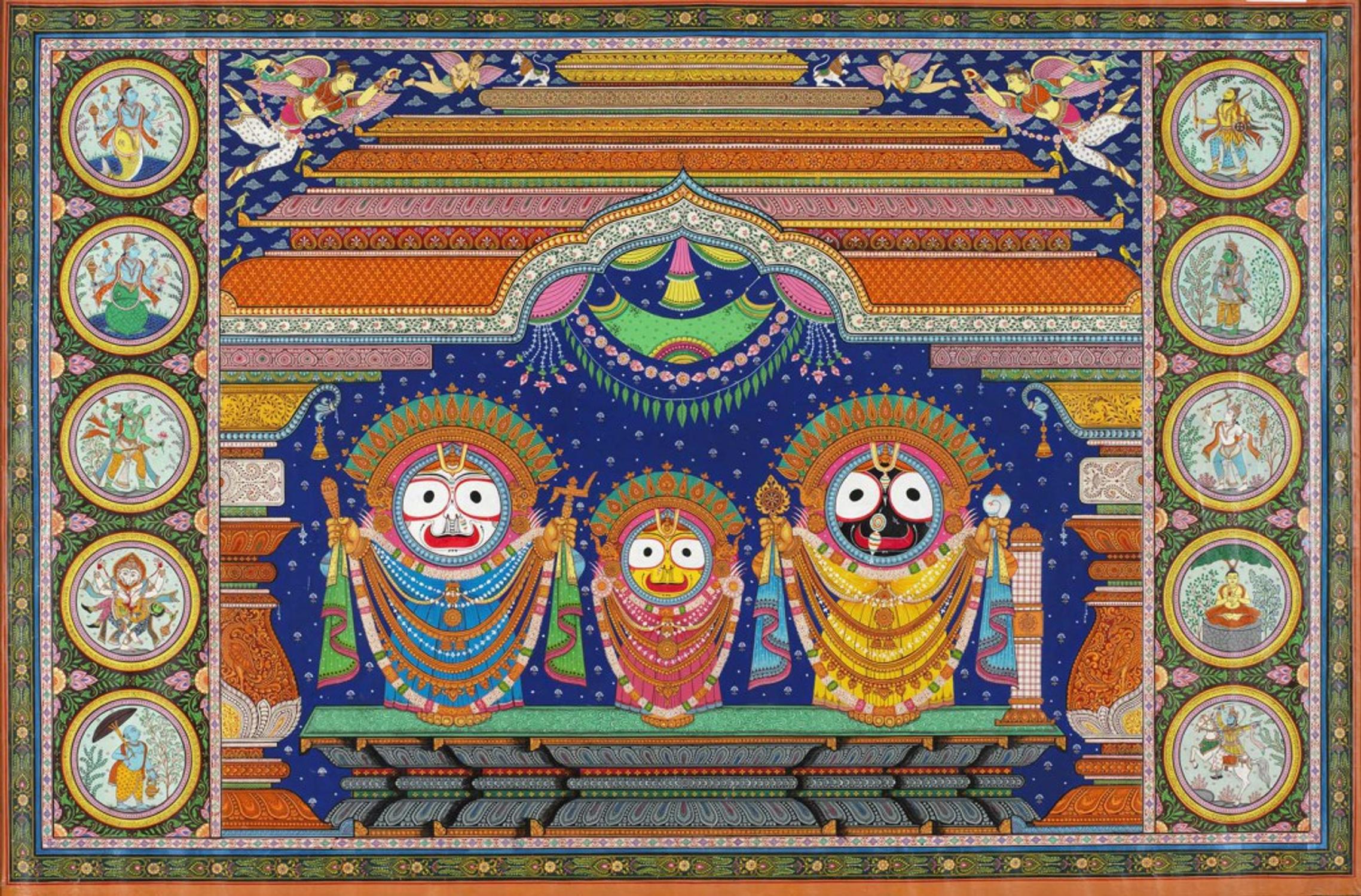

Brahmachari Nilesh, Inde

Inv. 2010.2.1

Jagannâtha, Nilesh Bramachari, 2009

Paint / cotton

H. 80 x L. 117 cm

Since his childhood, Brahmachari Nilesh has been naturally attracted to art. Despite growing up behind the slopes of the Mountain range of Orissa (India), far from any artistic influences, his talents were recognised by his parents, in particular his mother, who was the driving force behind his artistic development. After graduating in fine arts at the University of Behrampur, Orissa (India), Brahmachari Nilesh worked for several traditional masters, who initiated him into various techniques.

Under the guidance of the illustrious Kala Guru, the late Sri Dasarathi Maharana, teacher of the traditional art of Bhuvaneswar, he received detailed training in the Patachitra painting of Orissa, which uses exclusively handmade vegetable dyes, reputed to last for ever. He also learned to paint on palm leaves, a complex and elaborate technique necessitating long preparation. The palm leaves, once prepared, are engraved with a drawing using a lékino (Metal pen) and coloured with black dye made out of burned coconut. Production of a painting on a palm leaf can take between 3 to 12 months, depending on the degree of complexity of the work in question.

Brahmachari Nilesh has also studied other traditional our methods, such as Kashmiri, Tanka (Buddhist art) and Tanjur. He has practised wall painting and wood carving, as well as sculpture in stone and terracotta. Since he grew up in close contact with the natural environment and the tribal populations, his childhood impressions are often reflected in his works. His focus on spiritual research, the essence of existence, subtle but vital, is expressed through the themes treated in his painting. He has travelled throughout India, often on foot, with his sketchpad at hand, but always with the aim of returning and then painting on canvas: an experience that transcends art.

Brahmachari Nilesh has exhibited at different art festivals, in Hiroshima and Tokyo (May 2010), as well as at Art In Action in Oxford (July 2010). That same year, he was invited to exhibit his works in Saint-Pierre, Reunion, for the Dipavali light festival. Impressed by his productions, the Villèle museum decided to acquire six of his works.

Madhubani painting, India

Inv. 2000.4.8 - Tatoo painting, Devi MUDRIKA, 1999 - distemper / paper - 153 x 40 cm

"[...] Madhubani is one of the historical cradles of Indian culture, where ancient ritual practices have survived unchanged for centuries. Several traditions of wall and floor painting, created by women, were associated with these ritual practices and survived until very recently in their orthodox form.

[...] The ritual traditions of wall and floor paintings produced by women were still predominant in the 1960s, when paper as a surface for painting was introduced in Madhubani. When the paintings came down from the walls to be applied to rolls of paper, their expression became freer, even as they came to rise to greater challenges. Several women Madhubani painters, up till then limited by the restricted possibilities presented by the painting of patterns imposed by working on a fixed surface for a specific ritual event, started to exploit this opportunity of individual artistic expression and experimentation that was offered to them thanks to the availability of paper. Among the most talented women Madhubani painters taking advantage of the possibilities presented by painting on paper, we can name Ganga Devi, Mahasundari Devi, Sita Devi, Baua Devi, Anmana Devi, Chano Devi and Lila Devi.

The fact that the artists put an end to the repetitive reproduction of symbols, patterns and magical iconography linked to the purified ritual spaces that they had inherited in the context of a shared live tradition and the celebration of annual rites and rituals, progressively led to a distinctive form of artistic creation, both as regards the subjects treated and at the same time the creation of a new formal vocabulary. However, these women artists remain profoundly anchored in the ritual practices of the Madhubani ancestral traditions and their artistic transformation, leading to individual expression, is the very illustration of the complementary character of processes of collective tradition and individual expression.

Creative expression by artists from tribal and rural communities has always, though wrongly, been seen as the product of collective ethnic expression, the authenticity of which is considered to be dependent on the past. A ‘traditional’ or tribal artist living in modern times also has a contemporary facet, a notion reflected in the works of the artists on display in this exhibition. The history of contemporary Madhubani women artists demonstrates the way in which artists working on repetition, closely linked to their tradition, have responded spontaneously and with their entire sensitivity to the new possibilities offered thanks to the use of new materials and how they have embarked on the most remarkably innovative projects of Indian art.”

Jyotindra Jain, Director of the Crafts Museum, Delhi, "La peinture madhubani" (Madhubani paintings) (extracts). Exhibition catalogue for ‘Madhubani, art tribal de l’Inde’ (Madhubani, tribal art from India), Villèle museum, 2000

Collections by topics

Collections by topics